Words: Dr. Kausthub Desikachar, PhD

Yoga is often envisioned as a tranquil dance of bodies flowing gracefully on mats, or as quiet moments of breathwork under a rising sun. However, beneath the stretching and stillness lies a profound, intricate philosophy encompassing all aspects of life, including what is on your plate.

Nutrition is not a side note to Yoga. It is foundational. The ancients understood that food quality directly shapes the quality of thoughts, emotions, and ultimately, consciousness itself. Food is thus not merely fuel; it is a bridge between the gross body and the subtle mind—a carrier of Prāṇa, the life force.

In the grand tapestry of Yogic living, the key principles of diet help transform eating from a mundane act into a sacred ritual, each bite a step on the path to inner harmony. Though there are many principles to consider, we offer the six most important ones.

1. Plants, Prana, and the Yogic Plate: The Power of the Vegetarian Diet

At the core of the Yogic approach to food stands Ahimsā, the timeless principle of non-violence. Extending compassion to all living beings naturally steers the practitioner toward a vegetarian diet.

The moral and energetic dimension

Consuming meat involves participating in the harm of sentient creatures, disrupting the inner harmony that Yoga seeks to cultivate. Yogic texts suggest that food carries subtle energies, and meat is believed to harbour tamasic vibrations— qualities of inertia, darkness, and heaviness that cloud the mind and slow spiritual progress.

On the other hand, a diet rich in fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds is imbued with Prāṇa—the very life force that animates the universe. Such foods uplift the body and mind, fostering clarity, lightness, and joy.

The Bhagavad-gātā’s timeless classification

The Bhagavad-gītā (17.8-10) elegantly divides food into three categories aligned with the three guṇas (fundamental qualities of nature):

- Sattvic foods are fresh, juicy, wholesome, and pleasing, increasing longevity, health, happiness, and purity.

- Rajasic foods are excessively bitter, sour, salty, hot, pungent, or dry, provoking restlessness and agitation.

- Tamasic foods are stale, decomposed, overripe, or impure, leading to lethargy and confusion.

A Yogi intentionally cultivates a Sattvic diet, understanding that such food nurtures the physical body and the subtle layers of mind and heart, creating a fertile ground for meditation.

Milk and moderation

Interestingly, classical Yogic diets often included fresh, ethically sourced milk, considering it highly sattvic. In traditional times, cows were lovingly tended, and milk was taken in small amounts, warm, sometimes spiced—nourishing yet light on the digestive fire.

2. Bless Before You Bite: How Food Becomes More Than Just Fuel

While modern nutrition zeroes in on calories and micronutrients, Yoga recognises another layer: the subtle energy of food, which thoughts, words, and vibrations can influence.

Blessing and offering

Many Yogic traditions begin a meal with a short prayer or mantra, offering the food to the Divine or acknowledging it as a gift of nature. Chanting verses such as “oṁ brahmarpanam brahma havir…” (Bhagavad-gītā 4.24) helps sanctify the food, purifying any negative impressions it may have picked up along its journey from farm to plate.

This act of blessing is more than ritual:

- It cleanses the food energetically, neutralising subtle “dark” vibrations.

- It shifts the eater’s attitude from entitlement or distraction to humility and gratitude.

- It tunes the mind to a higher frequency, preparing it for physical nourishment and spiritual grace.

- “You are what you eat”—energetically, too!

The Upanishads teach that the subtlest essence of food becomes the mind. This is why Yogis hold that food offered with love, prepared in a peaceful mind, and consumed in gratitude is a form of meditation, infusing the mind with serenity and sweetness.

3. Bath Before Bites: The Curious Case of Yogic Meal Timing

Among the lesser-known Yogic practices is the discipline of eating only after bathing, never before. This guidance flows from an intricate understanding of how cleanliness influences both physiological processes and subtle energies.

The reasons are multi-layered

- Physical cleanliness: Bathing clears away dirt, sweat, and environmental residues, preventing food contamination and enhancing digestive readiness.

- Energetic receptivity: A clean body is more open to absorbing Prāṇa from food. Just as we wouldn’t pour nectar into a soiled vessel, the body too should be clean before accepting nourishment.

- Mental calm: Bathing cools the nervous system, bringing a tranquil state that reduces mindless eating or greed-driven indulgence.

Conversely, eating and then bathing can disrupt digestion by diverting blood flow to the skin, weakening the Agni, or digestive fire—a critical concept in Āyurveda.

The classical daily sequence

Traditional Yogic routine (Dinacarya) beautifully integrates these insights:

- Rise before dawn (Brahma-muhūrta)

- Evacuate bowels, clean mouth

- Perform gentle cleansing Kriyas

- Bathe, then meditate or chant

- Prepare and eat the first meal with calm and gratitude.

It’s a rhythm that combines hygiene, serenity, and digestive vitality—an artful choreography long before modern biohacking.

4. Fasting by Another Name: Yogic Wisdom vs. Modern Intermittent Fasting

If you think intermittent fasting is a hot new trend, Yogis might chuckle in lotus position. They’ve practised mindful meal timing for millennia, not for six-pack abs, but to conserve Prāṇa for higher pursuits. What we consider intermittent fasting today is basically nothing but a regular eating habit that has been around for thousands of years.

Two meals a day: elegant simplicity

Many Yogic systems advocate eating just two times daily:

- One main meal, sufficiently nourishing.

- One lighter meal to sustain energy. This approach gives the digestive system ample rest, minimises toxic build-up (Āma in Āyurveda), and keeps the mind steady rather than constantly chasing tastes.

Spiritual vs. purely physical aims

While modern intermittent fasting highlights insulin sensitivity or autophagy, Yogic fasting goes further:

- It reduces worldly attachments and cravings, strengthening discipline.

- It makes more Prāṇa available for meditation, as digestion is energy intensive.

- It teaches contentment, lessening the grip of the senses.

Fasting Days

Days like Ekādaśi (the 11th lunar day after each full and new moon) are traditionally observed with complete or partial fasting. Far from punitive, these days are seen as opportunities to cleanse body and mind, turning attention inward.

The Seasons Know Best: Eating Local and Temporal

Long before “farm to table” became a culinary movement, Yogis honoured the intelligence of nature through seasonal and local eating, a principle rooted in Āyurveda’s concept of Ṛtucarya.

Why local and seasonal?

- Foods grown in the same climate and soil that nurtures your body resonate at the same vibratory frequency, supporting harmony.

- Seasonal foods naturally balance the dośas. Cooling, hydrating fruits like melons arrive in summer; grounding, warming roots and spices emerge in winter.

The Caraka-samhitā, a foundational Āyurvedic text, devotes extensive passages to guiding diet by season, understanding that nature knows best what our bodies need at each turn of the earth’s orbit.

6. Personalisation: Yoga, Ayurveda, and Your Unique Blueprint

A crowning strength of the Yogic approach to diet is its profound respect for individual constitution.

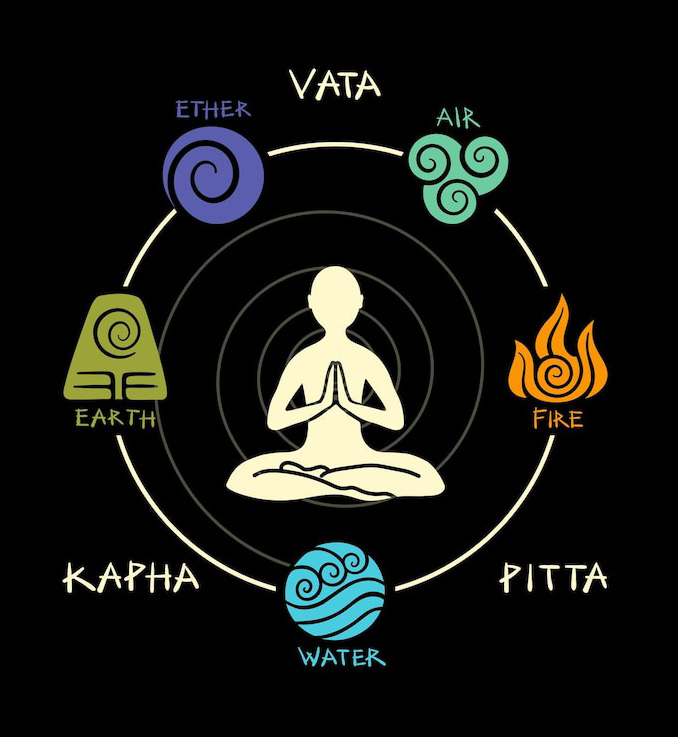

Constitution (Prakrti)

Āyurveda teaches that each person has a unique balance of Vāta (air/ether), Pitta (fire), and Kapha (earth/water) energies. Accordingly:

- A Vāta type (light, dry, cool) thrives on warm, moist, grounding foods.

- A fiery Pitta finds balance with cooling fruits and mild spices.

- A heavy Kapha benefits from light, pungent, bitter dishes that invigorate digestion.

Age and health considerations

- Children need more anabolic, building foods (sweet, nourishing).

- The elderly require easy-to-digest, warming preparations.

- Those recovering from illness may receive specific Rasayanas (rejuvenating foods/herbs).

Yoga thus gracefully avoids rigid universals. Instead, it champions a living intelligence that honours where you are, who you are, and what you need right now.

The Last Bite: From Plate to Peace

The Yogic view is profoundly simple yet radically transformative:

“As is the food, so is the mind; as is the mind, so is the life.”

Each morsel is more than carbohydrates and amino acids—it is vibration,

consciousness, and karma. Eating with awareness aligns our bodies, minds,

and spirits with the very rhythm of the cosmos.

So tomorrow morning, as you sip your warm lemon water or cradle a bowl

of fresh fruit, pause. Bless it. Savour it. Know that you are not just feeding

muscles and bones.

You’re feeding compassion. You’re nurturing clarity. You’re cultivating a mind

that, like the quiet pond, can reflect the moon of enlightenment.

And perhaps, that is the sweetest taste of Sattva of all.

SIMPLE PRACTICES TO EMBODY YOGIC NUTRITION

If you’d like to taste this ancient wisdom in daily life, here are small but powerful ways to begin:

Choose fresh, Sattvic foods— fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, gentle spices.

Bless your meals, even silently, turning eating into a sacred exchange.

Eat mindfully, slowly, joyfully, free from screens and stress.

Listen to your digestion, letting true hunger—not habit—be your guide.

Favour seasonal and local produce, building harmony with your surroundings.

Try gentle fasting once in a while, not as punishment, but as a loving reset.

Kale and Karma: The Sweet Taste of Sattva

A Sample Yogic Day of Two Meals

Morning Ritual

- Wake early (Brahma-muhūrta, ~4-6 am)

- Drink warm water (with lemon or ginger)

- Bathe before eating to cleanse body & mind

- Practice Yoga Āsana, Prāṇāyāma, meditation

Main Meal (Late Morning, 10 AM – 12 PM)

Eat your largest meal when your digestive fire is strongest.

Grain & Legume Base:

- Rice or light mung dal khichdi with mild

- spices (turmeric, cumin, coriander)

- Or small chapatis with ghee

Cooked Seasonal Vegetables:

- Sautéed or steamed with gentle spices

Digestive Aids:

- Coriander-mint chutney

- Small bowl fresh homemade yoghurt or diluted buttermilk with cumin

Finish with Fruit (after some time):

- Ripe papaya, mango, or banana

Drink:

- Warm water or herbal infusion (no iced drinks)

Light Evening Meal (Before Sunset, 6-7 pm)

Lighter to support restful digestion overnight

- Vegetable Soup or Stew:

Pumpkin, carrots, zucchini, celery, cumin, ginger

- Optional Small Portion of Light Grain:

Little millet or barley if more sustenance is needed

- Warm Digestive Tea:

Fennel, tulsi, or chamomile

Before Bed

- Warm turmeric milk (or almond milk with cardamom)

- Or simply warm water

- Brief gratitude prayer or mantra

Core yogic Eating Tips

- Bless food before eating — transform it into Prasad.

- Eat seated, calmly, with full attention.

- Leave 3-4 hours between meals & before sleep.

- Eat only when genuinely hungry, not from habit.

- Favour fresh, seasonal, local, sattvic foods.

The Yogic Food Spectrum

(Sattvic, Rajasic & Tamasic at a Glance)

Sattvic Foods

– “Foods that increase life, purity,

strength, health, joy and cheerfulness.”

— Bhagavad Gita 17.8

– Fresh, natural, light & nourishing

– Builds clarity, calmness,

compassion

Examples:

• Fresh fruits, vegetables, and leafy

greens

• Whole grains (rice, barley, wheat,

millets)

• Nuts, seeds (soaked or lightly

roasted)

• Legumes (mung dal, lentils)

• Fresh milk, ghee, and homemade

yoghurt

• Mild spices: turmeric, coriander,

cumin, fennel

• Honey, jaggery in moderatio

Rajasic Foods

“Foods that are too bitter, sour, salty, hot, pungent, dry, burning…” — Bhagavad Gita 17.9 – Stimulating, increases drive, restlessness

- Good in moderation for active duties, but agitates the mind

- Examples:

- Coffee, tea, and chocolate

- Strong spices (chilli, garlic, onions)

- Pickles, sour foods, and excess salt

- Fried & oily dishes

Tamasic Foods

“Foods that are stale, tasteless, decomposed, putrid, impure…” — Bhagavad Gita 17.10

- Heavy, dulls the mind, breeds inertia

- Leads to lethargy, confusion

- Examples:

- Meat, fish, eggs, and alcohol

- Fermented, canned, and overly processed foods

- Leftovers older than a day

- Too many sweet or stale pastries

- Excessively heavy fried foods

A Gentle Reminder

Eat to nourish both body and mind. What we eat becomes our thoughts, and our thoughts become our destiny.

Leave feedback about this