ŚĀKTAPRAMODAḤ OF ŚĀKTAPRAMODAḤ OF DEVA NANDAN SINGH

Words: Stephanie Renee dos Santos

Today in the yoga and meditation sphere there’s a lot of focus and conversation around sacred feminine wisdom, practices, and teachings. One reason for this is a large percentage of practitioners today are female. It’s natural to begin to inquire as to where are women’s voices and examples within these ancient transformative traditions? Also, with the ever-growing environmental concerns around the planet and a current world paradigm which doesn’t seem to be able to effectively address these issues, where is there a belief system that can assist?

Longstanding, South Asia has been a repository and steward of sacred feminine wisdom, giving rise to a tradition called Śāktism which is a body of practices, knowledge, and ritual traditions that have thrived unimpeded for thousands of years. Originally, teachings were transmitted orally and then eventually written down too. It’s a living wisdom stream that recognizes ultimate Consciousness as female in essence, of which all beings, the earth, and all manifestations are but different faces of the one Supreme Sākti, meaning energy or power. Sākti is the all- pervading dynamic force of Consciousness, the universe, the cycles of birth, life, transformation, and death. The lineage views the relationship between humans, vegetation, animals, spirit, and divinity as one unified whole where nothing is separate, for all things are expressions of One Consciousness.

Today, with ongoing environmental and equality issues, empowering and liberating Sākta teachings are more than relevant. As we, as a collective humanity, seek ways to transform our lives and world in order to meet the challenges of the day in both daily living, caretaking for the planet, and the pursuit of ultimate Truth. Śāktism is all-inclusive of dualities such as male-female, soul-body, transcendent-immanent and considers

nature as divine. Devī, defined as Goddess, is considered to be the cosmos itself – the embodiment of energy, matter and soul, and the motivating force behind all action and existence in the material universe. The masculine and the feminine are aspects of the divine and all-encompassing reality. Uniquely in this wisdom stream, Sākti is not in consort with the divine masculine but the source of the masculine. It is a tradition that’s given rise to the longest and largest ongoing Goddess festival on the planet called Navarātri which goes by many names such as Duressha, Dashin and Durgā Pūjā depending where you are in South Asia.

Navarātri is a celebration that occurs four times a year. The fall festival being the most attended during the months of September or October in honor and worship of Durgā Devī. The nine-night and ten-day festival happens at the turn of the seasons. Goddess worship in India reaches back to the Bronze Age between 3300- 1300 BCE to what is now referred to as the Harrapan Civilization or the Indus Valley Civilization. This society flourished in the northern region of India in what is now Pakistan. From the archeological sites in this area clay figurines of female figures have been found in large quantities, along with clay seals depicting a woman entity. Honoring and revering the feminine as sacred and supreme has an ancient and long history in India and South Asia. Female-rooted reverence has flourished for thousands of years as verifiable in these artifacts.

Śāktism has given rise to multiple wisdom texts. One key collection of Sākta Tantrā practices and wisdom manuals is the Śāktapramodaḥ of Deva Nandan Singh. The collection of teachings was compiled in the nineteenth century by Raja Deva Nandan Singh Bahadur. He was an aristocratic Zamindar who amassed a significant amount of Sākta texts in his private library. The first edition of the Śāktapramodaḥ, translating as “Joy of Goddess Worshipers” was published in 1891. His motivation for the creating the compilation was to re-invigorate Kalī worship in his region in India, to counter fraudulent Sākta teachers of his time, and for the benefit of worshipers to have what we’d call today a “go-to” manual

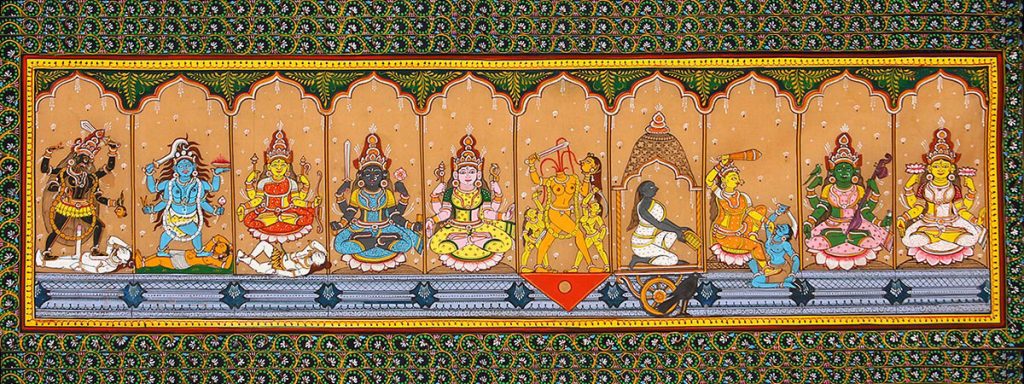

for this body of wisdom and practices. A second edition followed in 1894 and now Dr. Madhu Khanna’s 2013 newly edited edition. Dr. Madhu Khanna, the most recent editor is a distinguished scholar of Indic Religion, who earned her PhD from Oxford University in Hindu Sākta Tantrā. She is the author of multiple books and academic papers, providing reliable translations and the unpacking of the knowledge of these ancient wisdom texts for the benefit of yoga and meditation practitioners worldwide. Her PhD dissertation, “The Concept and Liturgy of the Sricakra Based on Sivananda’s Trilogy” (Oxford University, 1986), was one of the first contemporary comprehensive examinations of the Śrīkula lineage of Sākta worship in India. The edited compendium of the Śāktapramodaḥ of Deva Nandan Singh contains sixteen tantric ritual manuals written in Sanskrit. It brings together under one book jacket, ten texts on the Mahāvidyās, along with the Kumārī Tantrā, and five tantras of the Five Gods called the Pañcāyatana. It is an authoritative portal into the origins and worship of the Dāsa Mahāvidyās “Ten Great Goddesses of Transformation”. The Mahāvidyās are a collective of ten female deities whose characterizations reveal and map the evolutionary phases of our psychic Consciousness. Each Goddess entity pointing out aspects of the “I-self” to be addressed, transformed, dismantled, and the empowerments of each stage of Consciousness awakening to itself through the vehicle which is “you” as exemplified in these ten personifications of Devī: Kalī, Tārā, Soḍaśi, Bhuvaneśvarī, Chinnamastā, Tripurabhairavī, Dhumavatī, Bagalāmukhī, Mātaṅgī, and Kamalā. Khanna’s 2013 edition, gives a ninety-one-page authentic summary in the introduction in English, touching on the Kumārī Tantrā

and Pañcāyatana and offers an in-depth overview of the Mahāvidyās. High lighting one-by-one each Goddess, exploring historical cultural roots, unique traits, and interrelationships between the Goddesses, along with specific ways to worship and carry out sādhana, defined as practice. Khanna’s presentation of the Mahāvidyās is revelatory and insightful. Plus, she references her source texts, empowering each of us to seek further should one like to do so.

In addition, Khanna explains the step-by-step process of Devī Pūjā” Goddess Worship”, presenting the different stages and the sequence of practices that were derived from authoritative tantra ritual manuals. For example, the ten parts of Devī Pūjā: (1) Dhyāna, meditation of the deity; (2) Yantra, geometric expression of a deity and tool of meditation; (3) Māntra, transformative sound; (4) Pūjā vidhi, ritual practice; (5) Stotra, hymn of praise; (6) Kavaca, protective chant; (7) Hrhaya, the heart; (8) Upanisad, the secret doctrine; (9) Aṣṭakam, collection/ series of eight practice parts; and (10) Sahasranāma, the thousands names. This is helpful and useful for those who are seeking reliable written instruction to support a teacher or a Guru’s teachings on how to practice in this living wisdom stream.

Also, Khanna introduces the reader to the ancient practice of the Kumārī Tantrā, devotion to a living virgin child who is honored and recognized as the fullest form of embodied Sākti in human form. A tantra which abolishes all distinctions and barriers of class and societal position. It is a practice that can be carried out during Navarātri. Where each day, the devotee worships a different form of the Kumārī. A practice which is done in the presence of a child or adolescent girl from the ages of two to sixteen years old. It is a practice I witnessed in 2016 during Navarātri when I was at Ramakrishna Math Ashram in Belur Math on the outskirts of Kolkata in West Bengal in India. Where young women were dressed head-to-foot in red dresses, lovingly adorned with gold-colored bangles and refinery and actively revered by practitioners as the fullness of Mahāśakti, the Great Sākti, power and energy.

On each day of Navarātri, a tithi, meaning one daily cycle of a lunar month, a different Kumari form is practiced with and worshipped. The nine different Kumaris exemplify nine different powers of the Goddess Kumārī. The first Kumārī, aged two is worshipped as the full embodiment of the Goddess Kumārī herself, to dispel misery, poverty and enemies, and bestow long life and wealth. The second day the Kumārī, Trimūrti is honored, she who bestows the three aims of life: longevity, riches, and progeny. Day three Kalyani is worshipped, the realizer of all desires, giver of knowledge, victory and kingdoms. Next, day four is Rohinī, practiced with for healing and the cure of all diseases. Day five Kālika is honored for the dissolution of adversaries. The sixth day Chandikā for prosperity and abundance. Day seven, Sambavī, for enchanting and vanquishing adversaries, victory in battle, and removal of impoverishment. Durgā is celebrated on day eight, for bringing happiness and the final removal of enemies in

all forms. The ninth and final day, Shubhadrā is worshipped for expelling bad luck and the fulfillment of all desires. All the practices and intentions are done as ritual worship to a living young female each day with various invocations and practices. She is honored as the living embodiment of the fullness of the Goddess Kumārī.

Thereafter, Khanna shares about the “Tantras of the Five Gods” called the Pancayatana, with an exploration of this grouping of five deities: Durgā, Śivā, Gaṇeśa, Sūrya and Viṣṇu. The tantras of this collection are organized with Durgā coming first, exemplifying how she is poised in the most prominent position, reflecting the Sākta supremacy and source as feminine.

The introduction concludes with an explanation of the mode of worship of the five Pañcāyatana Tantras which exposes how the dominant Smārta tradition, which played a significant role in the development of the Saṃkhyā tradition and Pātañjalayogasūtra, incorporated aspects of tantric practice into its worship. Thus, Khanna challenges the popular assertion that tantric practices were peripheral forms of worship and in opposition to the mainstream religious beliefs of India. We can understand, through Khanna’s explanation, that this isn’t the case, that in fact, there was an intermingling of the two. There is still an enormous corpus of Sākta texts to yet be thoroughly examined and translated and Khanna encourages continued research in this sphere.

The book’s jacket cover depicts an exquisite Mahāvidyā painting in the Mithilā style painted by Bhattoji Jha. The Śāktapramodaḥ of Deva Nandan Singh is an important and authoritative tantra reference text and support for Sākta sādhana for anytime of the year and especially during committed practice during Navarātri.

Professor Dr. Madhu Khanna is a distinguished scholar of Indic studies, specialising in Hindu Shakta Tantra based on the Kashmir Shaiva tradition. Her work bridges traditional knowledge systems with contemporary cultural contexts. She is the founding chairperson of the Tantra Foundation and Tantra Foundation Library, New Delhi, and has held prominent academic positions, including Director of the Center for the Study of Comparative Religions and Civilizations at Jamia Millia Islamia and Tagore National Fellow at the National Museum. A few of her other publications: ‘The Tantric Way’ (1977) co-authored with Ajit Mookerjee; ‘Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity’ (1994). http://www.tantralibrary.com/

Leave feedback about this